What Makes a Classroom an Effective Learning Environment?

by Dr. Tom Perks

In early 2012 the Learning Environment Evaluation Working Group (LEEWG) embarked on a pilot project to examine classroom space at the University of Lethbridge. Initiated by the Teaching Centre, the impetus for forming this collaborative group of staff, faculty, and students from across campus was to promote the improvement of current teaching and learning spaces at the University and to inform the process of planning for future classroom construction and renovation. The project represents an initial attempt by the group to empirically explore the importance of the relationship between a classroom’s physical environment and the perceptions of instructors and students who work and study in that classroom. After all, given that our physical surroundings have a profound influence on our behaviours, it makes sense for an institution devoted to higher learning, and especially one that is devoted to quality undergraduate teaching, to engage more closely with classroom space and to understand how the learning environment can be designed or modified to improve instruction and learning. The LEEWG sees itself as playing a collaborative and leadership role in developing relevant evidence-based criteria to inform classroom design at the University of Lethbridge.

This article focuses on one aspect of this project: an examination of instructor and student perceptions of the physical aspects of the learning environment in room L1050, and the effect, if any, that comprehensive changes to this classroom had on these perceptions. As such, we are especially interested in comparing perceptions of the physical environment of L1050 before and after changes to the room.

Recent research (Hill & Epps, 2010) certainly suggests that students are perceptive of changes to classroom environments, and may be more “satisfied” (p. 77) with courses taught in improved classrooms. Of course, while student satisfaction is an important consideration, what the group is also interested in is whether improvements to a classroom environment have an impact on student learning and, by extension, the quality of their academic outcomes. Put differently, as Lizzio, Wilson, and Simons (2002, p. 27) ask, do students “do well” or “not so well” regardless of the environment? It makes sense that a similar question could be asked of instructors: does the classroom environment influence the quality of instruction, or is the quality of instruction similar regardless of the room? Although we do not test these questions directly, the results reported below are suggestive of significant and tangible improvements to both the instructor teaching and student learning experiences as a result of the changes to the classroom design of L1050.

We should note that, early on in the project, L1050 was chosen as a “locus of convenience” in that (a) it is a space that could be physically reconfigured (to the extent that was required) relatively easily and inexpensively; (b) similar courses, in terms of content, level, and number of students were scheduled in this classroom for both fall and spring terms; and (c) in both terms a sufficient number of instructors teaching in the classroom were amenable to participating in this study. The classroom itself is a non-tiered rectangular 30’ x 44’ (9.1m x 13.3m) room that is designated to accommodate 60 students. The room contains movable tables and chairs, usually configured into rows oriented parallel to the length of the room (Figure 1)

Data Collection

The instructor and student samples upon which our findings are based were taken from courses scheduled to be taught in L1050 in the Fall 2012 and Spring 2013 terms. Prior to the beginning of each term, instructors teaching in L1050 were contacted to inquire if they would be interested in volunteering to participate in the study. Out of a total of fourteen different classes that were scheduled to be taught in the Fall 2012 and Spring 2013 terms, four instructors in each of the Fall and Spring terms agreed to participate in the study. Those who agreed were from a relatively diverse group, representing a diverse variety of courses from different faculties. After an instructor had volunteered to participate, students enrolled in her or his course were informed of the study and that their participation was completely voluntary. All instructors and students were guaranteed confidentiality, and each participant provided informed consent prior to their involvement in the study.

Information from instructors and students was gathered using a variety of data-collection methods, including an in-class survey, instructor interviews, focus groups for both instructors and students, and in-class observations, with the same methods being used in both the Fall 2012 and Spring 2013 terms. A total of 281 students responded to the in-class survey (153 and 128 in the Fall and Spring, respectively), representing a 79% response rate, and a total of 14 students participated in the focus groups across the two terms. Importantly, all of the data collected in the Spring followed substantial changes to the physical environment of the room (Figure 2), completed during the Reading Week break in February.

Classroom Modifications

The changes made to L1050 were primarily based upon comments from faculty and students, collected in Fall 2012, regarding aspects of the room that they reported as either disadvantageous to instruction/learning or adequate but could be improved upon. Although most respondents were generally satisfied with the room, criticisms of the room tended to focus on the size and location of the whiteboard, inadequate sightlines and lighting, the relative inflexibility of the room configuration, the number of student desks in the room, the size and location of the instructor workstation, and the size and location of the digitally projected image. We additionally referenced innovative design recommendations for active learning spaces (Beichner, 2008; Brooks, 2011; Walker, Brooks, & Baepler, 2011), taken from a comprehensive literature review examining classroom space conducted by the group in Summer 2012. With this information in mind, the following changes were made to L1050:

- reversing the room orientation front-to-back

- reducing the seating in the room to accommodate a maximum of 40 students

- re-configuring the student seating into four rows of six trapezoidal tables accommodating ten seats per row; with a centre aisle in each row (three tables of five seats on either side)

- extending the continuous usable length of the whiteboard at the (new) front of class to 20’

- moving the whiteboard forward to just in front of the pillar on the (new) front wall

- replacing the existing digital projector and screen with two 80” LED high-definition display monitors located on either side of the whiteboard

- reducing the size of the instructor workstation and placing it just to one side of the centre aisle

- adding a SMART PodiumTM and document camera to the classroom technology suite

- painting each side wall blue

Findings

Comments from both instructors and students elicited during the interviews and focus groups were for the most part consistently positive about the room changes. In particular, both instructors and students responded very favourably to the reduced number of tables/chairs and the reconfiguration of the furniture on either side of a centre aisle – commenting on an improved sense of engagement with class activities and enhanced instructor-student and student-student communication. Additionally, in classes where collaborative or cooperative work was important, the ease of forming smaller work groups and then re-forming for whole-class instruction was noted. Instructors who had previously relied on adjacent “break-out” rooms outside of the classroom commented additionally on the efficiency of being able to have students work in groups (or “pods”) within the classroom itself. Furniture reduction and reconfiguration was also noted to have improved student sightlines to both the instructor and presentation materials. Having a continuous length of easily visible whiteboard was also positively highlighted (the previous configuration of the room had two white boards, separated by a pillar). Instructors responded very favourably to the smaller workstation, and particularly commented on the added value of the SMART PodiumTM and document camera. Interestingly, the colour of the walls was cited as having a consequential favourable influence on the aesthetic of the room as well as positively impacting the effectiveness of the room lighting – eliciting comments that the room now seemed “warmer,” “more intimate,” “more stimulating,” “more comfortable,” and “less institutional”; while the lighting appeared to be “less harsh.” Reversing the room orientation was noted by both instructors and students as reducing the disruption and distraction caused by students entering and exiting the class, and easing traffic flow into and out of the room. Replacement of the traditional projector and screen, however, received a mixed reaction. While some instructors and students commented on improved image clarity and viewability, others reported two screens to be more distracting. Students particularly commented on the difficulty arising from viewing a monitor from one side of the room while the instructor was speaking from the centre or pointing to something on the other monitor.

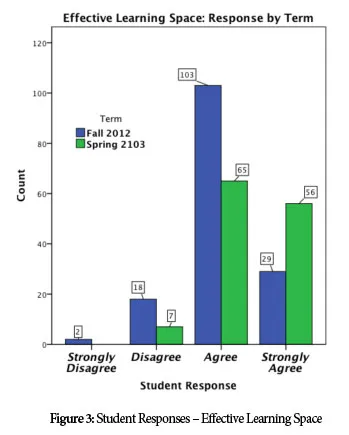

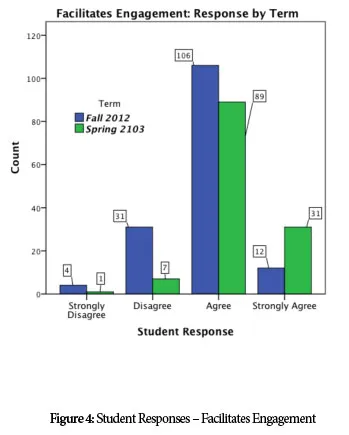

The findings from the student survey data support many of the comments reported above, in that they too indicate an almost consistently positive response to the room changes. For example, in response to the statements, “The classroom in which I am taking this course is an effective space in which to hold this particular course” and “The classroom…facilitates student engagement in the learning process”, Figures 3 and 4 clearly show a shift “upward” (i.e., away from “strongly disagree” and toward “strongly agree”) when the pre- and post-room-modification results are compared. We should note that preliminary analyses examining differences by age, gender, major, and year of study between the Fall and Spring samples of students were non-significant, so we have no reason to believe that these changes across terms were the result of cohort effects. Clearly, then, these results are suggestive that the changes made to the L1050 enhanced student engagement and made the classroom a more effective learning space. Statistically significant (p0.001) increases were also observed for questions asking students about how they generally felt about the room (from “hate it” to “love it”), whether they felt the room facilitated different learning activities, and whether the room was physically comfortable. Significant increases in reported perceptions regarding room configuration, sightlines, and the colour of the walls were also found. These general improvements to student perceptions are exactly what we’d expect if the modifications to L1050 enhanced it as a teaching/learning space.

Conclusion

What is obvious from the findings is that the initial results from this project indicate that the renovations have made a significant improvement to L1050 as a learning environment. Both the reported perceptions of instructors and students identified here as well as anecdotal feedback following the changes to the room suggest that a number of the changes have been well received and are perceived to favourably impact teaching and learning. Certainly, this preliminary data positively and significantly supports the changes made to particular features of the classroom, including:

- the room and furniture reconfiguration

- the reduction in the number of student spaces in the room

- improvements to the whiteboard space

- painting the side walls

Changes to the room configuration and the reduction in the number of desks in the classroom were particularly noteworthy for the overwhelmingly positive reception they received. We were fortunate in that both in the Fall and Spring terms there were no more than 40 students enrolled in any course scheduled to be taught in L1050, allowing us to make this modification (the classroom originally held 60 students). Reducing the number of desks clearly increased the flexibility of the room, allowing the desks to be moved with ease when necessary, whereas the room when arranged with seating for 60 was simply too congested to allow this. The less tangible but general sentiment regarding the “feel” of the room, in terms of things such as instructor movement and a sense of “congestedness” among students, was also improved. We might conclude from this that while L1050, when arranged to hold 60 students, passes the necessary building codes regarding occupancy, this does not mean that it necessarily passes what arguably should be considered more important pedagogical considerations. Given this, we are hopeful that the room configuration stays at 40 in the future.

The addition of paint to the side walls appears to have some of the effects we had hoped for, in that most who commented felt that adding some colour to an otherwise entirely white room improved the room’s ambiance. There was, however, an unanticipated effect in that, despite no modifications being done to the lighting, a number of students commented that the lighting in the room had improved, making the room brighter. Although considerations regarding what specifically is an appropriate room colour (or colour scheme) go beyond the scope of this preliminary study, our findings suggest that colour choices should not be relegated to a secondary consideration when designing a classroom. As well, it appears that numerous classrooms around campus could be improved in subtle ways with the relatively simple and inexpensive addition of paint.

Although the changes to L1050 were generally viewed quite favourably, not all of the changes necessarily were. As we noted earlier, the results were inconclusive regarding the replacement of the projector and screen with the two side-mounted LED displays. The fact that some students and instructors were receptive to the two displays, while others found the use of a second display to be distracting is important, as it speaks to the difficulty of doing classroom modifications. That is, while some instructors and students may perceive a particular change to a classroom positively, based on their personal teaching and learning styles, others may see it as detrimental. It may also be the case that a particular change to a room might enhance one aspect of the learning/teaching experience, but be detrimental in another way. For example, in this particular case, while the use of two displays appears to have significantly improved sightlines in the room, it also appears that the two displays may lead to students feeling more distracted and less “connected” to what is being presented on the display. Of course, the two displays were incorporated into the updated classroom design of L1050 to allow for more whiteboard space at the front of the room. Again, this is an example where improvement to one aspect of the classroom may have potentially been detrimental to another.

The findings reported in the present article are, of course, only preliminary. We hope to further validate these findings, and explore more closely the changes made to the room’s technology (e.g., the use of two LED displays) in the Fall 2013 term. As such, the project is ongoing, both in terms of our examination of L1050 but also more generally in terms of our examination of other learning spaces across campus. For example, we’re concurrently in the process of examining, and hoping to improve, L1060 as a learning space.

As the university engages in planning for both the construction of new teaching spaces and the renovation of existing spaces as part of its ongoing Destination Project, the LEEWG sees the examination of classroom design as vital to this process. Given the preliminary findings from L1050, we are particularly interested in exploring classroom designs that accommodate a broad spectrum of instructional methods, from traditional to emerging delivery styles, and to promote designs that enhance teaching and “promote learning excellence” (Mitchell, White, & Pospisil, 2010, p. 15). In short, the group feels that classroom designs should be supportive of different teaching and learning styles, support individual as well as collaborative learning, be inclusive, be motivating, as well as be flexible as the University adapts to changing needs, both pedagogical and technological. Of course, such goals are diverse, and not necessarily easy to accomplish in any one room. The LEEWG, in collaboration with the Teaching Centre, is hopeful to take an active role to help ensure that these goals are, to the best extent possible, met at the University of Lethbridge.

References

Beichner, R. J. (2008). The SCALE-UP Project: A student-centered active learning environment for undergraduate programs. Paper commissioned by the Board on Science Education, National Research Council, National Academies. Retrieved from http://physics.ucf.edu/~bindell/PHY%202049%20SCALE-UP%20Fall%202011/Beichner_CommissionedPaper.pdf

Brooks, D. C. (2011). Space matters: The impact of formal learning environments on student learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(5), 719-726.

Hill, M. C., & Epps, K. K. (2010). The impact of physical classroom environment on student satisfaction and student evaluation of teaching in the university environment. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 14(4), 65-79.

Lizzio, A., Wilson, K., & Simons, R. (2002). University students’ perceptions of the learning environment and academic outcomes: Implications for theory and practice. Studies in Higher Education, 27(1), 27-52.

Mitchell, G., White, B., & Pospisil, R. (2010). Retrofitting university learning spaces: Final report. Surry Hills, Australia: Australian Learning and Teaching Council.

Walker, J. D., Brooks, D. C., & Baepler, P. (2011). Pedagogy and space: Empirical research on new learning environments. Educause Quarterly Magazine, 34(4).