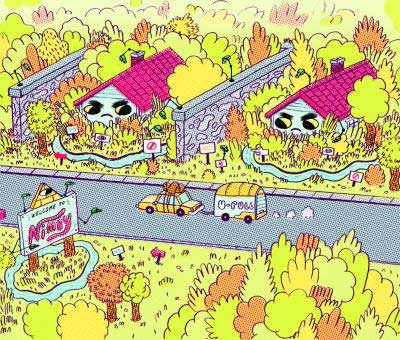

That's why an interdisciplinary group of researchers at the University of Lethbridge has teamed up to study the NIMBY phenomenon, its impact on home renters and homebuyers in Lethbridge, and ultimately, how to combat the problem.

Kim Smith* (*Kim Smith is a pseudonym) is well acquainted with racism, especially when it comes to the Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) phenomenon. For most of her adult life, the long-time Lethbridge resident has encountered landlords who wouldn't rent to her because she is First Nations. Those who would accept her were often slumlords that didn't maintain their properties or respect their tenants.

Smith's story isn't uncommon. Dr. Yale Belanger, a professor of Native American Studies at the University of Lethbridge, says NIMBY is happening in Lethbridge. That's why he's working with his U of L colleagues, Dr. Jo-Anne Fiske (Women's Studies) and Dr. David Gregory (Health Sciences), to study the phenomenon.

The team has interviewed dozens of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in Lethbridge to better understand how NIMBY works, its impact on First Nations people and what can be done to eradicate the problem.

"Wherever people feel there might be social changes or impacts on the value of their home, or encounter people with whom they're not familiar, you'll find NIMBY," explains Fiske.

For victims, NIMBY means more than struggling to find a place to live.

"The sense of exclusion, marginalization and discrimination has a major impact on a citizen's well-being," she says.

The effects of the phenomenon are harsh, and as Gregory notes, this kind of discrimination has psychological consequences.

"It undermines one's self-worth and self-value," he says.

NIMBY has a long history in Lethbridge. Belanger, who's trained as a political historian and is the project's principal investigator, points out that until the 1860s and '70s, many Americans came to the Lethbridge area thinking they could set up homesteads, farms and ranches free of any interaction with First Nations people.

"They brought with them the notion that native people were a scourge of the frontier," says Belanger. "Not everyone exercised those ideas outright, but because they were in place, there was a strong disconnect between the first white settlers and the First Nations people."

Over time, the area's First Nations people were forced onto reserves by the government, further dividing people. Even after the government stopped monitoring and controlling their movements, most of them continued to stay on the reserve, only coming into town to do errands.

The first urbanization of Aboriginal people in Lethbridge happened in the 1970s. Now 40 years later, there are about 5,000 Aboriginal people living in the city. After close to a century of segregation, two groups that have traditionally had little interaction are now living next door to each other, explains Belanger. In many cases, frustrations have reached a boiling point, resulting in some residents being openly hostile to their First Nations neighbours.

But Belanger is quick to point out that the First Nations people weren't the only ones to be openly marginalized in Lethbridge. Around 1911, for example, a town council proclamation led to the consolidation of the Chinese business owners working in Lethbridge onto Second Ave. South where Chinatown is located today.

This "history of ghettoization," as Belanger puts it, is alive and well today with NIMBY. The discrimination comes in many variations and degrees. During interviews with the researchers, some people openly admitted that they didn't want Aboriginal people living next to them, but in many cases, prejudice was far subtler.

"Some people actually considered themselves supportive of First Nations groups, even though they didn't want them living nearby," says Belanger. "The stereotypes are entrenched, and people may not realize they're projecting a racist or discriminatory attitude," says Belanger.

Fiske agrees.

"Attitudes run deep," she says, and often these attitudes are rooted in fear. In the case of a native women's transition centre slated to be built in Lethbridge's Stafford area a couple of years ago, protesters expressed concern for neighbourhood safety, operating under the assumption "that native women posed a threat to the city," says Fiske.

She and the other researchers are actively working to bring their research to the community in the hopes of stimulating social change. In the last year or so, they've presented their work at academic conferences, community groups and city council.

While NIMBY is a phenomenon many Aboriginal people experience, there's been precious little research on it. In fact, urban Aboriginal people are often overlooked by researchers.

"In Canada, the majority of research with respect to First Nations people focuses on reserves," says Gregory. "But, with increasing numbers of Aboriginal people moving to the cities, there's a misalignment."

He'd like to see more work on urban Aboriginal people and is working with his two colleagues to establish the Regional Centre for Urban Aboriginal Research.

"We have been networking with the local First Nations and Aboriginal communities in an effort to establish working relationships to enhance the University of Lethbridge's research capital within the local urban context," Gregory explains.

In addition to doing work with, about and for Aboriginal people, the research centre would bring together researchers from different disciplines, much like the NIMBY project.

"It's more comprehensive, with multiple perspectives coming to bear on a phenomenon," he says.

All of the researchers stress that the research isn't about pointing fingers at Lethbridge's citizens and painting the city as a racist place.

"We've all chosen Lethbridge; it's our home. It's not simply a research project – we're pursuing this research for the betterment of the community," says Belanger.

For more information on the Regional Centre for Urban Aboriginal Research, visit: www.urbanaboriginalresearch.com

For a look at the full issue of SAM in a flipbook format, follow this link.