Recent waves of immigration have led to a burgeoning bilingual population in Canada and second-language programs offered by the public education system have flourished in response.

The ability to speak a second language at a level that approaches native-like proficiency can positively affect academic and career success. However, graduates of second-language programs often produce speech errors that impair how well they are understood and sometimes lead to stereotypical judgments of their capability.

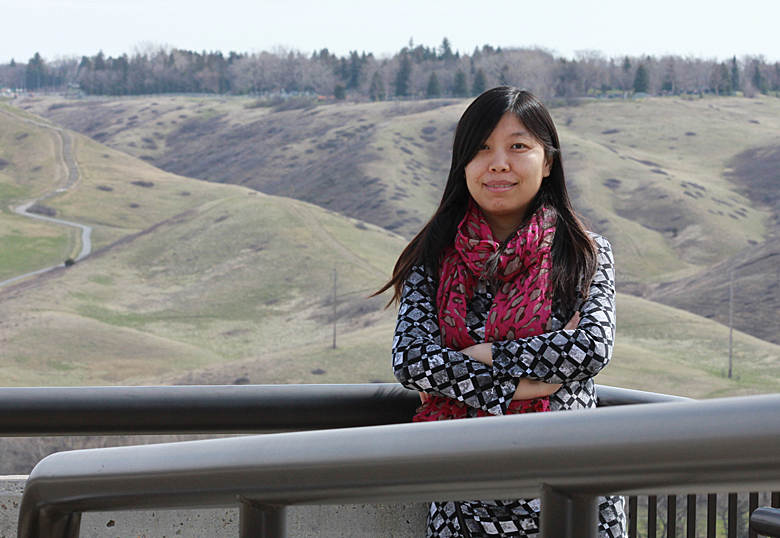

Now, thanks to $150,000 in funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Dr. Fangfang Li, a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Lethbridge, will be able to examine the factors that might influence speech errors. Li hopes to better understand the origins of such speech errors after she found some rather puzzling results from research she conducted with elementary-aged children in local French Immersion programs.

“In my past research, I looked at students in Grades 1, 3 and 5. At the time, we thought students in the higher grades should make fewer speech errors than students in lower grades but that’s not the case,” says Li. “We found that, if students make pronunciation errors when they are in Grade 1, it’s going to persist in Grade 5. They’re not getting substantial improvement over time.”

As Li pondered possible reasons for the finding, she hypothesized that local children in French Immersion programs continued to make the same speech errors because they most likely have an Anglophone background and are learning a second language that isn’t the dominant language in the community. These factors limit opportunities to speak French outside the classroom.

Li and fellow researchers from the University of Alberta and the University of Montreal have designed a further study to test out that hypothesis. Working with a colleague from the University of Montreal, one part of the study will have native French speakers evaluate students’ speech production and identify areas that need improvement. This information can then be used by teachers to design better educational materials.

“Once we obtain the normative data, we can then use it as a reference to design standard tests,” says Li.

In her previous study, Li spoke with school administrators who indicated a concern that no standard testing is available for students who are native speakers of English who acquire a second language such as French.

Another part of the study, done in collaboration with the University of Alberta, will look at a bilingual Mandarin Chinese and English program in Edmonton where the curriculum is divided equally between English and Mandarin.

“The student body is also divided so that native speakers of Mandarin Chinese and native speakers of English are mixed in the same classroom,” says Li. “That’s the kind of opportunity that French Immersion students, say in Lethbridge, don’t have. They don’t have the opportunity to talk to native speaking peers on a daily basis.”

Li expects that English students who have more opportunities to talk with native Mandarin-speaking peers and teachers will produce more accurate Mandarin speech as they move into the higher grades.

“If the Mandarin-English bilingual program proves to be better, I think it may be time to think about whether we can combine students from Anglophone backgrounds and Francophone backgrounds in the same school so they can learn from each other,” says Li.